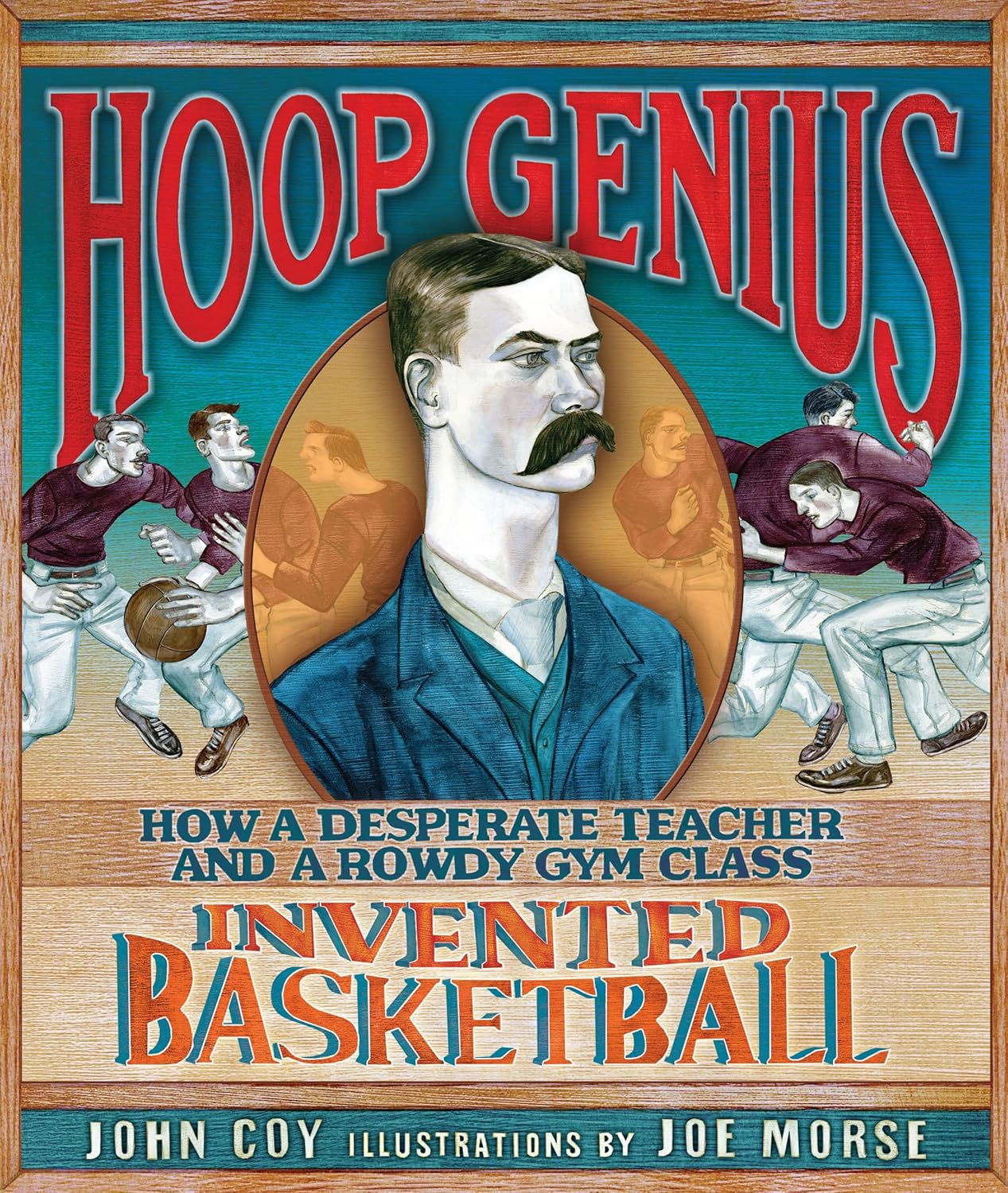

Story by John Coy, Illustrations by Joe Morse

Hoop Genius

How a Desperate Teacher and a Rowdy Gym Class Invented Basketball

Taking over a rowdy gym class right before winter vacation is not something James Naismith wants to do at all.

The last two teachers of this class quit in frustration. The students—a bunch of energetic young men—are bored with all the regular games and activities. Naismith needs something new, exciting, and fast to keep the class happy—or someone’s going to get hurt. Saving this class is going to take a genius.

Discover the true story of how Naismith invented basketball in 1891 at a school in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The Horn Book (starred)

This thrilling account of the birth of basketball is more a biography of the game itself than of its creators. The story begins with one James Naismith taking over an unruly gym class that had already run off two predecessors. He tries playing favorite sports indoors, but by the time they get to lacrosse not a player remains without some form of bandage. He needs a game where “accuracy was more valuable than force.” And so, in a Massachusetts gymnasium, basketball is concocted. Coy understands the power of detail—only one point was scored in the very first game—and his tight focus on the game’s initial season is immediately engrossing. Spare, precise language reflects the game’s welcome sense of order as well as its athletic appeal. Morse’s kinetic paintings, at once dynamic and controlled, fill the spreads, capturing the game’s combination of power and finesse. And the stylized figures and restrained palette of blue, brown, purple, and gray fix the proceedings in the nineteenth century. Naismith’s abiding respect for his students’ irrepressible energy plays an important role in the invention of the game, and the book credits the entire crew (“James Naismith and that rowdy class”) with the creation, adding a nuanced understanding of the value of sports and teamwork. An author’s note and selected bibliography offer additional information, and a you-are-there facsimile reproduction of the original thirteen rules of basketball adorns the endpapers.

NY Times

Sports origin stories are surprisingly scarce in picture book land, despite the obvious appeal. Coy’s story about the dawn of basketball in 1891 is a bit sparse with detail, but nonetheless offers an interesting account of the factors that went into devising the game.

James Naismith, in despair over the rowdy gym class he taught in Springfield, Mass., wanted a sport that emphasized accuracy over force and minimized contact. There’s a bit of Otto Dix in Morse’s distinctive paintings, with their angular contours and somber, blue-tinted skin, which lends an incongruous, though not displeasing, coolness to the notably hot-blooded sport.

School Library Journal

In 1891, a teacher named James Naismith invented a game that was destined to become a national sensation. The boys’ gym class at his school was particularly rowdy. He needed to find an indoor activity for the energetic lads that was fun, but not too rough. Inspired by a favorite childhood game, he stayed up late one night typing the rules of his new game. With a soccer ball, two peach baskets, and the rules tacked to the bulletin board, Naismith introduced his idea to the unruly class the next day. In that first game, only one basket was scored, but the boys were captivated. During Christmas vacation, they taught their friends how to play basketball and soon its popularity spread across the country. Even women formed a team. By 1936, basketball became a recognized Olympic sport and Naismith was honored at the opening ceremonies. Morse’s energetic illustrations add an old-fashioned charm to the narrative. Readers will also want to examine the endpapers, a reproduction of the original rules of the game typed by Naismith. This entertaining and informative story will delight young sports fans.

Publishers Weekly

Coy (the 4 for 4 series) tells the story of basketball’s founding in 1891 directly and succinctly. Young teacher James Naismith takes over a gym class of unruly young men. When other organized games produce walking wounded, “Naismith felt like giving up but couldn’t. The boys in the class reminded him of how he’d been at their age—energetic, impatient, and eager for something exciting.” Thirteen rules, a ball, and two peach baskets later, he develops a new game that demands accuracy while tempering aggressiveness. The story’s dynamism comes from Morse’s (Play Ball, Jackie!) stylized prints, whose posterlike quality is amplified by the limited palette of blue, brown, and maroon. Lanky limbs stretch dramatically across the pages, a visual foil to Coy’s spare storytelling style. While it’s slightly disconcerting to have the students referred to as “boys” when they appear as mustached young adults, their grimacing, chiseled features in motion are attention-grabbing. This lively glimpse into the beginnings of a hugely popular sport concludes with a short author’s note and bibliography.

Background

When I was a boy I loved hearing the story of James Naismith and the first basketball game. As a basketball player, I appreciated the connection to the original game and how far it had come. I wrote HOOP GENIUS: HOW A DESPERATE TEACHER AND A ROWDY GYM CLASS INVENTED BASKETBALL because many people don’t know this amazing story and I wanted to share it with them.

From first draft to finished book, the project took nine years, and the research was interesting. The more I learned about James Naismith and the first game, the more eager I was to share the story with others. I was fortunate that Naismith had written about the events leading up to that game so that I could read his own words of how the game developed.

In order to have a better understanding of Naismith’s early life, I made a trip to Almonte, Ontario, his boyhood home. John Gosset was very helpful in showing me the material that had been collected including the original stone where Naismith had played Duck on a Rock. He also introduced me to John Dunn, a local historian, who remembered James Naismith coming to talk to his high school class. To see the stone on which Naismith had played and to talk to someone who had met him was thrilling and provided a direct connection to the story. I also stayed in the house that Naismith used to stay in when he made trips back to Almonte. Gradually, the story began to take shape.

In addition, I made a number of trips to Springfield, Massachusetts, the site of the first game, and I received assistance from Jeffrey Monseau, the archivist at Springfield College and from the staff at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. The YMCA was the organization that was most responsible for the spread of basketball, and I benefited from the Naismith materials at the YMCA archives at the University of Minnesota and the assistance of Ryan Bean.

One of the things I ask people to think about is what game they would invent if someone gave them that task. It’s still incredible to me that James Naismith invented a game that became so popular he lived to see it played in the Olympics. James Naismith said, “I want to leave the world a little bit better than I found it.” He did that through his teaching, his life, and his invention of this game that millions of people love. Thank you James Naismith and that rowdy gym class for giving us this great gift.